Announcements and Demos

-

Sign up for CS50 Lunch this Friday!

-

Final Projects are nigh! The specification has already been released, detailing the following checkpoints:

-

Pre-Proposal

-

Proposal

-

Status Report

-

CS50 Hackathon

-

Implementation

-

CS50 Fair

-

From Last Time

-

By now, you’re hopefully getting comfortable with the concept of a pointer, a memory address.

-

We learned that Valgrind is a useful tool for detecting memory leaks and abuses. A lot of its output is cryptic, but you should look for phrases like "invalid write" and "definitely lost" as hints to your mistakes.

User Input

-

sscanfis what the CS50 Library uses to get input from the user in functions likeGetString.

scanf-0.c

-

Take a look at a simple example of using

scanf, which is quite similar tosscanf:#include <stdio.h> int main(void) { int x; printf("Number please: "); scanf("%i", &x); printf("Thanks for the %i!\n", x); }

-

The first argument to

scanfresembles an argument we might pass toprintf(The "f" in both denotes "formatted"). The second argument is the address ofx, thus empoweringscanfto actually modify the memory in whichxis stored. -

This program behaves as expected if the user provides a number as input. However, if the user provides a string or any other non-numeric input, the program behaves strangely. One of the things the CS50 Library provides is some error checking so that if the user provides bad input, he or she will be prompted to retry.

scanf-1.c

-

scanf-1.cclosely resemblesscanf-0.c, but introduces one major bug:#include <stdio.h> int main(void) { char* buffer; printf("String please: "); scanf("%s", buffer); printf("Thanks for the %s!\n", buffer); }

-

A buffer is just a generic name for a chunk of memory, a place to store information.

-

The problem here is that

bufferis uninitialized. We didn’t ask the operating system for a chunk of memory in which to store the string the user gives us. If we run this program, it will probably crash with a segmentation fault.

scanf-2.c

-

One solution to the bug in

scanf-1.cwould be to allocate memory forbufferon the stack, as we do inscanf-2.c:#include <stdio.h> int main(void) { char buffer[16]; printf("String please: "); scanf("%s", buffer); printf("Thanks for the %s!\n", buffer); }

-

Here, you can see that

scanftreats the arraybufferas a memory address. We know that the address is for a chunk of memory of size 16 bytes. -

In what scenario might this program also be buggy? If the user provides a string longer than 15 characters (not 16 because we need at least one character for the null terminator), the program may crash with a segmentation fault.

-

How do we know in advance how much memory to request for user input? We don’t! The CS50 Library has some logic that reads user input one character at a time with

scanfand requests more memory whenever it runs out.

Structs

-

Let’s revisit the problem of storing information about a number of students. We might start off just declaring a few variables like so:

#include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { string name = GetString(); string house = GetString(); } * What if we want to store another student's information? Well I guess we need some more variables: + [source]

#include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h>

int main(void) { string name = GetString(); string house = GetString();

string name2 = GetString();

string house2 = GetString(); string name3 = GetString();

string house3 = GetString();

}-

Hopefully, this strikes you as bad design. In prior weeks, we solved the problem of storing numerous variables of the same types by using arrays:

#include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { string names[3]; string house[3]; }

-

This solves the problem of repetitive code, but introduces the problem of names no longer being directly associated with houses.

structs.h

-

To reduce code repetition but keep information tightly coupled, we can introduce a new variable type using syntax like the following:

#include <cs50.h> // structure representing a student typedef struct { string name; string house; } student;

structs-0.c

-

Now we have a type called

studentthat contains both pieces of information about a student. Filling in this information is quite straightforward:#include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> #include "structs.h" // number of students #define STUDENTS 3 int main(void) { // declare students student students[STUDENTS]; // populate students with user's input for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { printf("Student's name: "); students[i].name = GetString(); printf("Student's house: "); students[i].house = GetString(); } // now print students for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { printf("%s is in %s.\n", students[i].name, students[i].house); } // free memory for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { free(students[i].name); free(students[i].house); } }

-

studentsis an array of variables of typestudentad defined in thestructs.hheader file. -

We access element

iofstudentsby writingstudents[i], as with any array. To access the pieces of information within any givenstudent, we use dot notation:students[i].nameandstudents[i].house. -

Don’t forget that we need to free the memory that we allocated when we called

GetString! Technically, we should also be checking ifstudents[i].nameandstudents[i].house)are notNULLbefore we free them.

structs-1.c

-

Before we examine the code, let’s just make and run

structs-1.c. After we enter in some data and the program exits successfully, a file namedstudents.csvis created. CSV stands for comma-separated values, a very simple version of a table like you may have worked with in Excel. -

The code that creates this CSV file looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43

#include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> #include "structs.h" // number of students #define STUDENTS 3 int main(void) { // declare students student students[STUDENTS]; // populate students with user's input for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { printf("Student's name: "); students[i].name = GetString(); printf("Student's house: "); students[i].house = GetString(); } // save students to disk FILE* file = fopen("students.csv", "w"); if (file != NULL) { for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { fprintf(file, "%s,%s\n", students[i].name, students[i].house); } fclose(file); } // free memory for (int i = 0; i < STUDENTS; i++) { free(students[i].name); free(students[i].house); } }

-

Line 27 does the work of actually opening a file, specifying "w" as an argument to

fopento indicate that we want to write to this file (whereas "r" would indicate read mode).fopenreturns a pointer to aFILEobject. Instead ofprintf, we usefprintfto write to our file. -

Question: what happens when you try to free a

NULLpointer? Your program will probably segfault.

Storage

Hard Drives

-

Hard drives that aren’t SSDs (solid-state drives with no moving parts) consist of circular metal platters and magnetic heads that read and write bits on them. The 0s and 1s of files are stored by magnetic particles that are flipped with either their north or their south poles sticking up.

-

Somewhere on the hard drive there exists a table that maps filenames to their memory addresses. As you can with RAM, you can number all of the bytes of a hard drive so that each has a memory address. When you delete a file, say by dragging it to the trash can or even by emptying the trash can, the contents of the file may not actually be deleted. Rather, the file’s entry in the location table is simply erased so that the operating system forgets where the file was stored. Not until the 0s and 1s of the file are actually overwritten will the file’s contents truly be gone. In the meantime, the file can be recovered by software like Norton or by a program like the one you’ll write for Problem Set 5. Having been provided with the raw bytes of an SD card, you’ll be tasked with searching through them to look for the particular pattern of bits that identifies the start of a JPEG file.

Floppy Disks

-

Back in David’s day

[The turn of the 20th century?]

, another type of storage called floppy disks was popular. Functionally, these are very similar to hard drives in that inside their plastic casing, there is a circular magnetic platter. You can get your hands on it just by ripping off the metal tab. Be careful, there’s a spring in there! -

These days, the size of hard drives is measured in terabytes. A so-called "high-density" floppy disk can only store 1.44 megabytes, or roughly 1 millionth of a terabyte.

Linked Lists

-

Arrays are useful because they enable the storage of similar variables in contiguous memory. One downside of arrays is that they have a fixed size. Another downside is that there’s no easy way to insert something in the middle of an array. To do so, we would have to allocate memory for a copy of the array and then shift all the elements to the right.

-

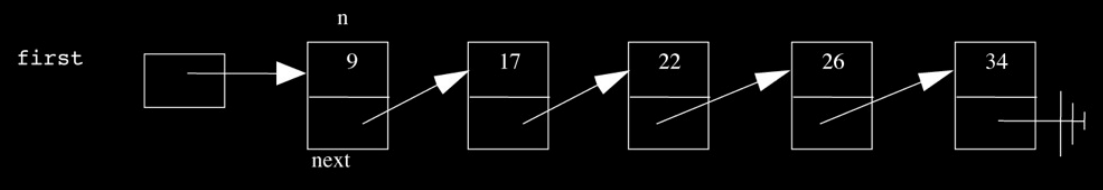

To solve the problem of fixed size, we’ll relax the constraint that the memory we use be contiguous. We can take a little bit of memory from here and a little bit of memory from there just so long as we can connect them together. This new data structure is called a linked list:

-

Each element of a linked list contains not only the data we want to store, but also a pointer to the next element. The final element in the list has the

NULLpointer. -

To implement a linked list, we’ll borrow some of the syntax we used for structs:

typedef struct node { int n; struct node *next; } node;

-

Pictorially,

nextis the bottom box that points to the next element of the linked list. Why do we have to declare it as astruct node*then? The compiler doesn’t yet know what anodeis, so we have to call it astruct nodein the meantime. -

There are a few linked list operations that will be of interest to us:

-

insert

-

delete

-

search

-

traverse

-

-

The search operation is actually pretty easy to implement:

bool search(int n, node* list) { node* ptr = list; while (ptr != NULL) { if (ptr->n == n) { return true; } ptr = ptr->next; } return false; }

-

searchtakes two arguments, the number to be searched for and a pointer to the first node in the linked list. We then declare a pointerptrthat we’ll use to walk through the list. Sinceptris a pointer to a struct, we use the arrow syntax (->) to access the elements within the struct. To advance to the next node in the linked list, we assignptr->nexttoptr. More on this on Wednesday!